Come with me across the legendary Aravalli Hills to Narlai, and the enchannting Rawlai Narlai, a private hotel in an ancient, historic fort

Last week, we dreamed and drifted at the romantic and ultra-luxe Lake Palace, floating on Lake Pichola in Udaipur. I’m so pleased you all loved it so much. Thank you so much for comments and messages and posts and emails and reposts… I hope you will visit the hotel one day.

This week, my adventure and exploration in western Rajasthan, northwest India, takes us to pretty villages where time stopped decades ago. Cows and bullocks wander past bazaars that spill out onto dusty streets.

Tribal women dressed in Paris couture-quality shocking pink chiffon ensembles shop for hand-made iron sickles and machetes for their farm work. Sacred cows step in front of rumbling buses and bicyclists pedal past.

I’m heading across the Aravalli Hills to a rare heritage hotel, the ultra-private Rawla Narlai set in a seventeenth-century former hunting lodge of the Maharajah of Jodhpur. It’s the twenty-year restoration project of two nephews of the Maharajah, one an interior designer and fashion stylist, the other a hotel entrepreneur. Rooms are designed and decorated in vintage Indian style, with charming hand-carved furniture, quirky architectural detail, authentic old paint hues, and hidden corners fragrant with frangipani for sunbathing or snoozing.

Days in India are vivid and every second is high-excitement.

Women’s costumes of hot pink, tangerine, indigo, neon lime green, turquoise silks and chiffon, are on the retina-dazzling end of the color scale. Sunlight is intense.

My camera can hardly get its mind around the intensity of shimmering daylight with deep dark contrasting and slanting shadows. The air is vivid with sounds of temple bells and flutes, and drums beat somewhere off in the distance. It’s seldom quiet. My eyes and ears tingle.

It’s as if I’ve tapped a tuning fork to my forehead, and amplified the frequencies of my senses. My brain is on high alert. It’s a very pleasant sensation, I must say.

The Lake Palace kitchen packed a delicious lunch of whole-wheat grilled vegetable sandwiches, crusts trimmed, as well as bananas and cookies, bottles of water.

My driver expertly heads north to this morning’s destination, Rawla Narlai.

It’s in one of the most remote regions in India, in the far Northwest.

I stop at hidden villages, encounter a thronging annual gathering of tribal leaders at an ancient temple, in the village of Desuri, and criss-cross a patchwork of rice fields.

I encounter a rare and privileged insider perspective, exclusively here.

Please read along and scroll down to see rare village scenes, as if Indian village life existed in its own time warp.

I arrived in Narlai, a farming village surrounded by mountains and lakes, late in the afternoon.

We drove through the town to a quiet corner beneath a granite mountain, its surface of cracked boulders seeming rather precarious in the sunshine.

We stopped at the twenty-foot high hand-carved gateway, and walked into the quiet retreat.

All is calm and tranquil, and I feel instantly at home.

The high walls wrap around. Rooms and suites are hidden behind archways, gates, walls, enclosed gardens, and drifts of white bougainvillea. Some rooms are perched on upper terraces, while others are accessed up stairs and beyond enclosed courtyards. It’s entrancing.

It’s a place for discovery, revealing itself in green-framed vignettes, overlooks and balconies. But behind closed doors, all is private, silent, and mysterious. I loved it.

Soon, a red-turbaned gentleman brought a tray with a teapot of Assam tea and a pretty flowered plate of house-made ginger cookies.

I sat on the terrace, sipping, and listening to distant bells.

Rawla Narlai: How did I discover it?

Two years ago, I stayed at Ahilya Fort in Maheshwar, Indore, central India. (Check the blog archives for that story.)

The owners are Prince Richard Holkar and his family.

Their private hotel, in a 15th century fort high above the river Narmada, is rare and beautiful and absolutely enchanting.

I asked Richard if he could recommend another heritage hotel in India, with the same feeling of integrity, history, and style he’d created at Ahilya Fort.

“Rawla Narlai in Jodhpur,” he proposed immediately. “It is very special.”

And so, two years later, I found myself at Rawla Narlai.

It’s a small private hotel built within the high limestone walls of a 15th century fort/hunting lodge of the Maharaja of Jodhpur. Rawla means fortress.

Ajay, the manager, showed me a portfolio of images, including a black and white shot of the fort twenty years ago, a crumbling shambles.

Over two decades, the nephews have restored, repaired and added to the original—all the while making it look as if it had never been touched. It’s artful, convincing.

My accommodations were a ‘suite’ with a sunny terrace, a sitting room, a bedroom with frescoed walls, and a large tiled bathroom.

Windows are ornamented with colored glass. Historic portraits of the royal Jodhpur family gaze down. Textiles are handblocked cottons. Curtains are the color of turmeric, dotted with posies.

Each suite and room is different. I propose that a guest should take a look at several rooms before settling in, if possible. Among the highlights are #13, a pretty room with a private terrace; #9, the prettiest room, with 16th century frescoes; #6 with lovely colored windows and a terrace. Selection may depend on the season, the temperature. (There’s a new addition. I prefer the old.)

The View at Sunset — A High Climb

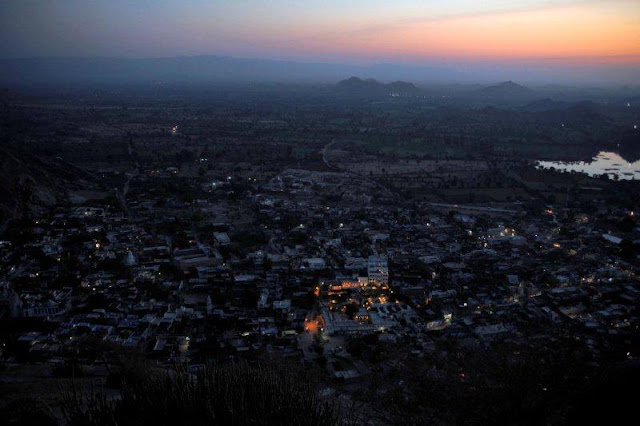

Narlai villa has grown up at the feet of a granite mountain that rises almost vertically, 1,500 meters, if I recall correctly.

The following day, Mr. Ajay, the friendly and helpful manager (a brilliant supervisor of the two-decade renovation and ongoing design of the hotel) proposed that I might like to climb the 750 steps to the top at sunset.

“You can view the whole region and see much of Rajasthan,” he noted.

And so, around 5.30pm, I set off with Lala Ram, who carried water, a Thermos of tea, and a few cookies in his backpack.

Some years ago, concrete steps were laid, zigzagging across the east side of the mountain, past shrines to Durga (the goddess of destruction) and cave shrines to various local goddesses, as well as a temple near the top.

Up and ever upwards we climbed, until suddenly we were on the curved shimmering crest, with vistas in all directions. Over to the west a 14th century fort scrambled across a rocky hill, and far down below was the hotel, its swimming pool glinting in the late afternoon light.

The sun, glowing in a golden haze, cast shadows across the landscape. I sipped Earl Grey tea and gazed off into the distance.

My guide suggested stopping at the temple on the way down. It was situated in a crevice, a natural catchment for fresh water.

I slipped off my shoes when we arrive there, just the two of us. My guide, who lives in Narlai, lit some tapers in a smoky niche of a Durga shrine. He passed his hands over the flames and then waved his palms over his head, across his chest and his body.

“Purification,” he said. “Here, do it.”

I quickly, without thinking, passed my hands over the leaping flames, palms down, and gestured over my head, my heart, and again above my head.

Just at that point, the orange-garbed priest entered the shrine. He rang a ceiling bell (to awake the spirits), chanted, and banged on a large drum.

I stood quietly, taking it in, listening, seeing, smiling.

I asked my guide if I should leave some money for the priest. “It’s not necessary,” he said. I put my hand in my small shoulder bag and took out some rupees. I left them discreetly beside the drum.

We headed down the mountain as dusk fell on the hillside and arrived back at the hotel in darkness. A tribal group were singing of love and beauty, loss and longing, accompanied by flutes, table, and a harmonium.

“Time and the Universe: Fundamental to Hindu concepts of time and space is the notion that the external world is a product of the creative play of illusion. Accordingly, the world as we know it is not solid and real but illusory. The universe is in constant flux. Time, past and present, is endless.” – Richard Waterstone, 'India The Cultural Companion’ published in 1985, MacMillan, London

An Evening Excursion

I travel very independently, and keep a very low profile. I have my own driver, find guides who are experts on the local culture, on architecture and history and the arts of the region. When I’m traveling, I love to see my friends and I arrange to visit academics, curator, and experts in fields relating to architecture and design. I seldom encounter non-Indian travelers when I’m traversing remote regions or walking, with no sense of déjà vu, into the painted rooms of moghuls or into a fusty palace that’s been closed up for fifty years.

But at Rawla Narlai, things were rather more impromptu. I happily accepted an invitation to take part in the hotel’s nightly Stepwell Dinner. We would travel beyond the village environs to a private garden preserve and the 17th-century stepwell. Stepwells are traditional Indian structure carved from the earth, like an inverted temple, to capture and save water in the rainy season. Stepwells, thanks to the importance of water, are also a place of powerful religious significance and have the formal architecture and significance of a temple.

We had to wait for the bullock carts. It turns out that during the way, the hearty bullocks are working in the fields and they had to be fed and watered and groomed after a hard day.

At the portal of the hotel, we climbed up onto the hand-carved cart, folk art, really, arrayed in hand-woven cottons. Some guest wore saris and turbans.

We bumped and jostled along the cobblestones, and finally disappeared into total darkness at the edge of the village. Above, in the dark sky, we could see the Pleiades, the sacred oxen, and I think I saw the Southern Cross (as you know, I grew up in New Zealand.) Orion? I'm traveling in the spheres.

It was a magical and charming evening. Two witty French couples and four adventurous English ladies, and Ellie, a young English student who was working as an intern at the hotel, settled in on four large sofas to listen to the flute.

We sipped white wine, and lime sodas, as the local musician seated in the stepwell created a mysterious atmosphere. I recall dinner, candles flickering, hours of laughter and delight.

Narlai Village Encounters

One morning, I set out with the hotel’s assistant manager, who lived with his family in Narlai, for an impromptu Narlai ramble.

While the community is primarily focused on farming arable fields surrounding the village, one of the locals told me that earlier generations had moved to Mumbai, become highly successful in business, and noq embellish their houses here and keep emotional ties to the town. They return for religious ceremonies and annual celebrations at the many Hindu temples that ornament the village with flag-draped shrines, turrets and spires.

In Narlai, I walked over to the charming village school to offer boxes of pens and pencils and pens to the teachers and pupils.

When I arrived, the eight-year-olds were sitting on the verandah, all neatly scrubbed, hair gleaming, bright blue shirts neat and ship-shape.

One of the boys stood and gave a heart-felt rendering, a capella, of the Indian national anthem. Wonderful.

The school, generously supported by Rawla Narlai, is very well-run, with maps and charts and images hung on walls, the teachers’ desks tidy and organized. I was happy to see the books, educational supplies and air of quiet and calm efficiency.

I always do a friendly talk with the children before I depart, reminding them how important education is, and especially urging the girls to stay in school.

“When the girls complete their education, you and your children will be healthier, and you will have a longer life,” I reminded them. It’s not unusual in traditional villages for girls to be married at fourteen. The girl, with a dowry, moves into the in-laws house, and her education ends. But times are changing. Girls now go to teacher training college or get a job in a nearby city (Jaipur, Jodhpur).

These school visits are always a highlight.

My guide asked if I would like to see inside a private house in the village.

We arrived at a large hand-carved doorway, and knocked. As we entered, a herd of sheep was restlessly waiting in the courtyard. Bales of wool freshly piled on one side affirmed that the skinny creature had just been shorn.

At that moment, the shepherd, in a magnificent red turban (symbol of his livelihood) greeted us, rounding up the sheep. He was taking them out to pasture.

I quickly jumped through the doorway so that I could photograph this rare moment.

The shepherd followed and the sheep, perhaps fifty of them, pushed forward to escape. I marveled at the shepherd’s white tunic and dramatic traditional moustache.

I captured some shots, and they were gone.

Turbans: different colors denote different livelihoods (red for shepherds), and family happenings (tie-dyed red and yellow for the arrival of a baby, yellow for a boy) and death (white). The basic fabric is 85 feet long.

On the Road to Narlai: Rajasthan Encounters

Narlai village is mid-way between Jodhpur and Udaipur.

It’s 140 km north of Udaipur, and around a hundred kilometers north of the Jain temple complex in Ranakpur.

From Udaipur, we sped a brief few miles on the highway to Jodhpur, and then turned off into the forested region around Ranakpur. We drove past villages with roadside weaving workshops crafting wool rugs, and headed into even more remote territory.

As we left the world of road signs and bumped along one-way roads, we arrived at the junction town of Shilpi, with a market in full throng.

I jumped out of the car to capture the scene. Cities like Jaipur and Delhi are changing fast, and many of the old endearing aspects are lost (camel carts lumbering through the center of town, cows wandering, knife sharpeners, are no more)—but time has stood still here.

Farmers’ wives in shocking pink chiffon ensembles buy rice and rope. Like many women, they cover their heads with a ten-foot-long length of chiffon, an orhni, to shield their faces from the gaze of strangers. The effect is mysterious, beautiful.

‘The children knew the bazaar intimately; they knew the kite shops where they bought kites and sheets of thin, exquisite bright paper. They knew the shops where a curious mixture of Indian tobacco and betel nut, and paan, done up in shiny green leaf bundles, was offered, and these with shelves of colored pajama strings and soda water. There were the grain shops, with sacks of wheat and rice and lentils, all spilling out, and the sweet shops, with their fragrance of sugary candies and cane sugar. They loved the glittering bangle shops, and the sari shops with cabinets full of sparkling saris trimmed with sequins and silvery fringe, as well as shops selling hand-forged farm tools, cans of oil, and bundles of ropes and wires. Some shops sold everything, in a vivid and dusty jumble.” — The River, by Rumer Godden, published 1946, London

As we drove on through the countryside, I saw throngs gathering outside a painted temple. Police with batons stood at the side of the road keeping control (or perhaps protecting them).

I ran from the car, and asked a policeman if I could take photos. “Yes, but not in the temple,” he said.

With permission, I snapped a tribal group arriving for a weekend of prayer, meditation and homage to gods and goddesses.

I entered the temple with the crowds (the only non-Indian person there) and was invited to meet the tribes three priests. Again, they invited me to hold my hands above the sacred flames, and wave them to purify my head and body, a kind of benediction.

It was such a privilege to be invited, to be welcomed, and to sit on the floor with a group of women, one of them holding my hand.

Finally, it was time to head to Narlai.

“Beautiful were the moon and stars, beautiful were brook and bank, forest and rock, goat and rose beetle, flower and butterfly. It was beautiful and delightful to go through the world like this, so aware, so open to what was near, so without distrust. Now Siddhartha was there, he belonged to it. Light and shadow ran through his eyes, and star and moon ran through his heart.” from ‘Siddhartha’ by Hermann Hesse (1877-1962). This translation by Joachim Neugroschel, 1999)

All images of Narlai village scenes, Rajasthan villages, and the thumbnail image of the hotel, and architecture by Diane Dorrans Saeks, exclusive to THE STYLE SALONISTE.

Images of the evening excursion to the step well, and interiors of the hotel courtesy Rawla Narlai, used with kind permission, exclusively on THE STYLE SALONISTE.

www.rawlanarlai.com

The website is currently being updated for the coming season.

Rawla Narlai is associated with India’s first heritage hotel, Ajit Bhawan, in Jodhpur. www.ajitbhawan.com